On Opinion Polls, #OperationPrimeMinister , bans and regulations

By Akshay Kanoria

Election time in India is ripe for all sorts of allegations and “sting” operations. Lately, both electronic and social media has been abuzz with insinuations that opinion polls in India are manipulated to suit particular a political parties, or even the highest bidder. A recent sting by TV channel News Express showed how several polling agencies, notably Yashwant Deshmukh-led C-Voter, were willing to manipulate poll predictions to suit their client.

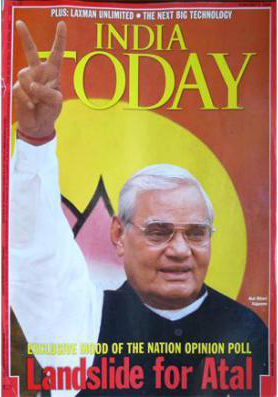

The Congress party, which has been at the receiving end of almost all opinion polls in the last few months, promptly demanded a ban on polls. The AAP appeared circumspect in comparison, demanding only that a new law be written to regulate such polls. But such reactions from politicians and public intellectuals are nothing new. Ever since the first prominent poll published by India Today prior to the 1980 election, opinion polls have been a controversial subject. Political junkies may recall a 2004 India Today cover shot of a beaming Atal Behari Vajpayee flashing the “V” sign, with a caption that read “Landslide for Atal.” Ever since that debacle, opinion polls in India have been widely discredited and mistrusted.

The Congress party, which has been at the receiving end of almost all opinion polls in the last few months, promptly demanded a ban on polls. The AAP appeared circumspect in comparison, demanding only that a new law be written to regulate such polls. But such reactions from politicians and public intellectuals are nothing new. Ever since the first prominent poll published by India Today prior to the 1980 election, opinion polls have been a controversial subject. Political junkies may recall a 2004 India Today cover shot of a beaming Atal Behari Vajpayee flashing the “V” sign, with a caption that read “Landslide for Atal.” Ever since that debacle, opinion polls in India have been widely discredited and mistrusted.

So what specifically are the gripes against opinion polls?

The most frequent complaint is about the sample size. The critics ask how a survey of only a few thousand (or even tens of thousands) of voters can be used to predict a result for a country of over 1.1 billion people, especially as complex and diverse as India. The answer is that the main ingredient for a successful statistical sample is not size, but representativeness i.e. how closely does the make up of the sample match that of the population it is supposed to be predicting?

Going beyond the sample size, it is also vital to pay attention to the margin of error within the poll. With a 3 per cent margin of error and 95 per cent confidence, a simplified understanding is that if you

repeat the same poll 100 times, in 95 of those repeats you’ll get results within 3 percentage points of your original numbers. In other words, you can be 95 per cent correct, or 5 per cent off the charts. In most opinion polls, pollsters use a margin of error of 4 per cent. Think of the margin of error as a pollsters reality check.

Additionally, most pollsters worth their salt will usually have a detailed break up of the polling methodology. For instance, the CSDS-Lokniti surveys (broadcast on CNN-IBN’s Election Tracker) come with detailed methodology for each state, showing the gender, class and caste break up in the survey versus recent census figures. A close match means that the survey is more likely to be accurate. Further, the actual questions, and the manner in which they were asked, matter as well. Again, looking at the methodology is a good place to start. When a survey is not transparent about methodology that should usually set off alarm bells. C-Voter is quite opaque about its methods, which probably explains a lot.

But what about polls that may have been conducted with a sound methodology but are purposely tweaked to mislead the viewer? This after all is the main complaint, the one with most substance and the one used to justify banning or regulating opinion polls. Again, the default option seems the simplest: look at the pollsters’ track record. The empirical nature of polls makes it easier for the viewer to judge for himself. There is a need to look at the prediction, and contrast it to the real outcome of the election, whether in vote share, seat share or both. Surveys that have a decent track record are worth trusting, while those that have a bad track record are easily discredited. Contrast polling agencies like Lokniti to C-Voter, and the results speak for themselves – if not with the exact numbers, then at least with the vote shares and general trend.

Another aspect of polls that requires understanding is the difficulty of translating vote shares into seat share. In a first-past-the post system with multiple parties and shifting alliances, two plus two often equals five. Many pollsters have been unfortunate in getting the vote predictions right, but stumbling on translating those into seat predictions. Sometimes, a mere two per cent difference can mean a difference more than ten times larger in seat terms. Further, all-India vote shares mean little, and the results need to be calculated state-by-state, region-by-region. That is one reason why the recent trend of focusing intensely on key states is a positive one.

Evidence that suggests opinion poll results affect voters’ behavior is slim, at best. Ironically, the only way one would judge that would be to conduct an opinion poll or survey. There is also this rationale: if you ban opinion polls because they are biased, the only information people have to go on is the direction of the blowing wind. It should be up to the viewer to judge whether a journalist’s ideas, based on anecdotal evidence is any better than that of a scientific (or even semi-scientific) survey.

When it comes to regulation of polls, just like with other regulations in India, the main question is who exactly will regulate the opinion polls? In a society that competes at a national level at the game of who-can-get-offended-first, it won’t be long before a pollster will find himself stuck between several rocks and hard places. The pollster might also find himself stuck in an exhausted legal system for months or years until they have to bend to whatever power is more favorable to them. There is also the fact that opinion polls in India are a terribly costly exercise that earn little money and regulation would be a burden that most pollsters can ill afford.

Consider also the widely prevalent intolerance for freedom of speech and expression, as well as for social science research in India, and the judiciary’s terrible track record in protecting the same. Couldn’t ministers like Sushil Kumar Shinde, who recently threatened to “crush” all opposition media, freely interfere with opinion polls when they are unfavorable to his or her party? And let’s not forget about the estemeed Justice Katju either. Why not simply trust the voter to be smart enough to judge for him/herself? Why not trust the TV channels and newspapers to care enough about their own credibility to ensure good polls? Perhaps it’s time for our citizens to start trusting their intelligence, and make their own choices. But in order to make choices, one has to first have them.

With inputs from Isheta Salgaocar

_____________________________________________________________________

Akshay Kanoria is a student at the University of Pennsylvania.